Why is understanding the physical implementation of memory useful?

Data compression

I recently [talked] about the moment when Yandex.Trainings put me on the spot. The last problem in this contest can be reduced to a BFS on a state graph. I got into it in a minute, spent two more on the code. And? My first submit got MLE (memory limit error). I thought: “Okay, I’ll fix it”. I optimized the code and… I got MLE again! On a different test, but there is no difference. All the time of the contest I was beating myself up over it, thinking: “What the hell is this?”. But it didn’t work. I guess sometimes even I can be wrong…

A couple months after that, I went back to the task, looked at it with fresh eyes and came to the conclusion that I was doing everything right! Mostly the task was passed in C++, and few people had encountered this problem. But by chance I still came across a .py solution that passed all the tests! And it implemented exactly what I tried, except for one thing. The only thing that made the solution different was that the description of a vertex of the state graph was compressed from a tuple to a single integer. It is conceptually impossible to describe a graph vertex with less than 3 numbers. However, given that each of these three numbers is guaranteed to be in a known small range, it is possible to encode all numbers with one! In fact, this approach exploits an interesting feature of the hardware:

And how we can use it? Let’s take a look…

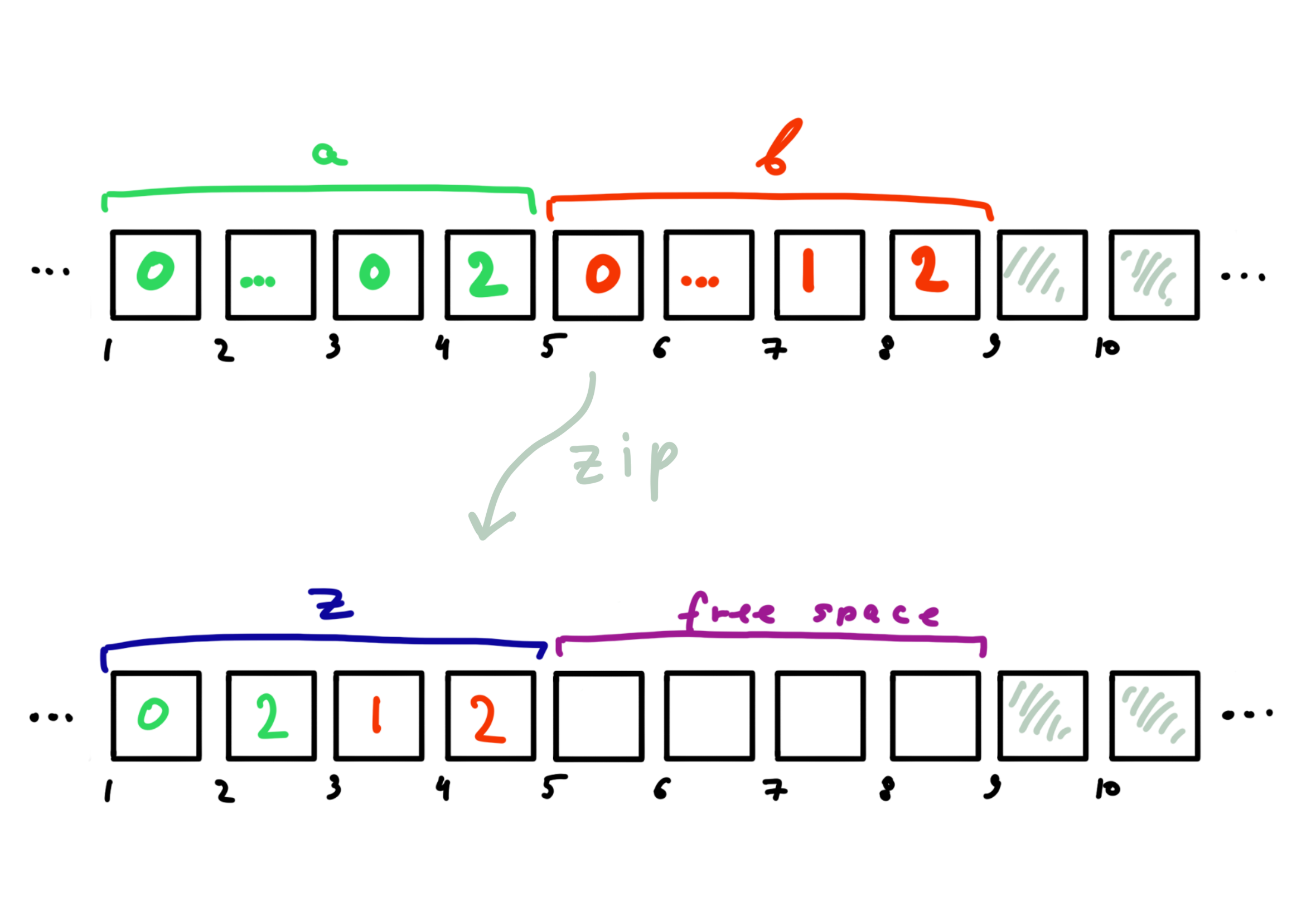

Suppose we have numbers \(a\) and \(b\), each of which is in the range \([0; \, 10^d - 1]\). Then both of these numbers can be represented by a single number \(z\) as follows \(z = zip(a, b) = a \cdot 10 ^ {d} + b\). If \(d=2\), \(a=1\) and \(b=12\), then \(z=zip(a, b) = 112\). By the number \(z\) we can always recover \(a\) and \(b\) as follows:

def unzip(z: int, d: int) -> Tuple[int, int]:

a = z // (10 ** d)

b = z % (10 ** d)

return a, b

due to a large number of non-significant zeros.

Although asymptotically the occupied memory remains the same, at large sizes the savings of even a factor of constant can be extremely noticeable!

*note that we assume all numbers are positive, otherwise we would need an extra bit.

Padding

Now we has convinced that studying the features of physical storage of objects in memory can be useful. However, now we will get acquainted with an even more interesting technique.

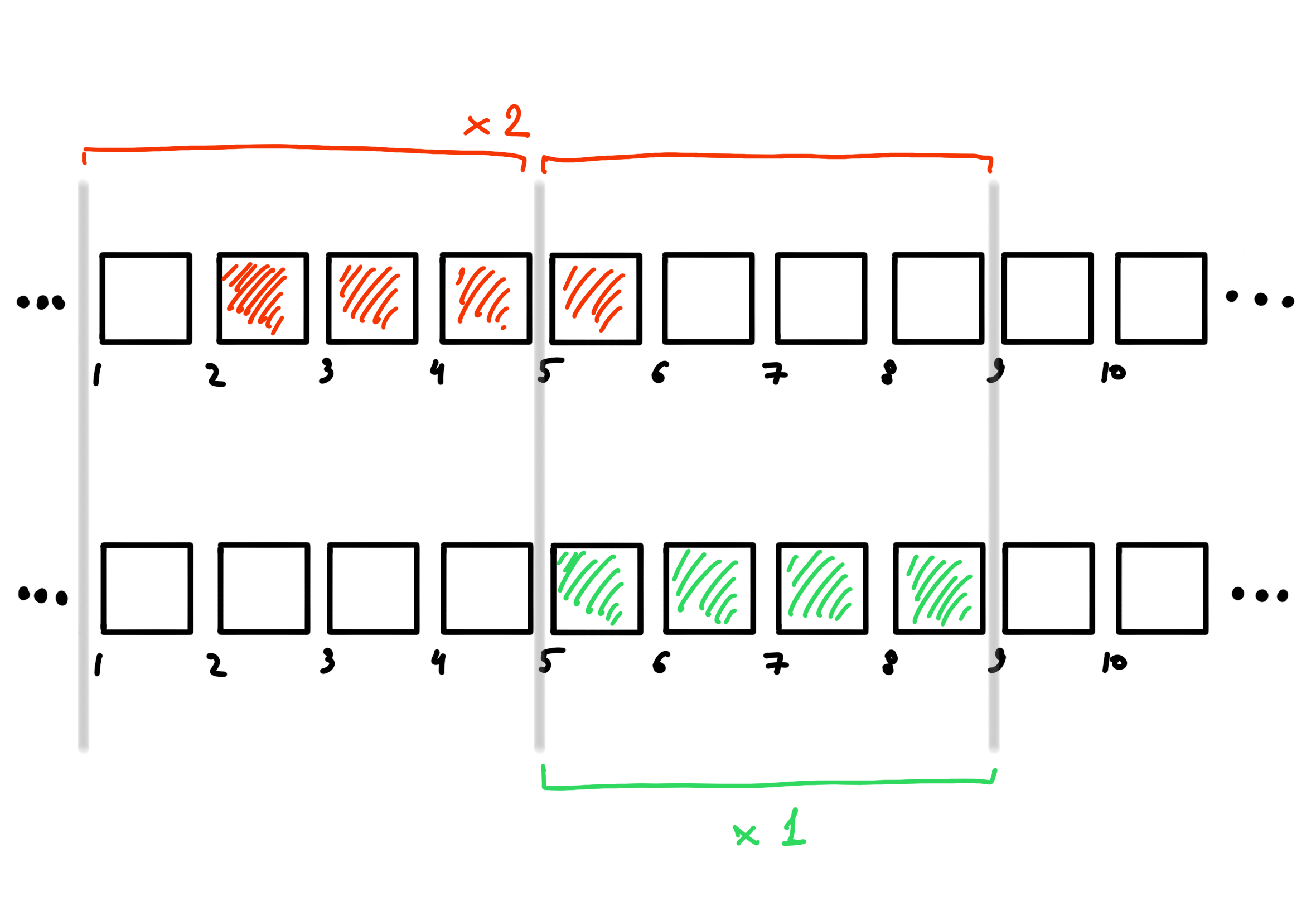

In the real world, the hardware reads several consecutive bytes (often 4) at once on each read operation. Moreover, on a number of architectures, it can only read 4 bytes from a position that is a multiple of 4. That is (when indexing bytes from 1), on some architectures it is basically impossible to read bytes [2-5] at a time. In this case, if we want to store an integer of size 4 bytes, the most efficient way to store it is to place it in consecutive 4 bytes starting at a multiple of 4. Why? Because it’s the only way we can read all the bytes of a number, spending only 1 read operation (see picture below). Any other way of storing information would take more! And the most efficient way to store a \(b\) byte number is to arrange it starting at the byte whose number is a multiple of \(b\) (the reason for this phenomenon is already very technical and we will omit it). Arranging objects so that they satisfy this condition is called alignment.

may be required if bytes are misaligned.

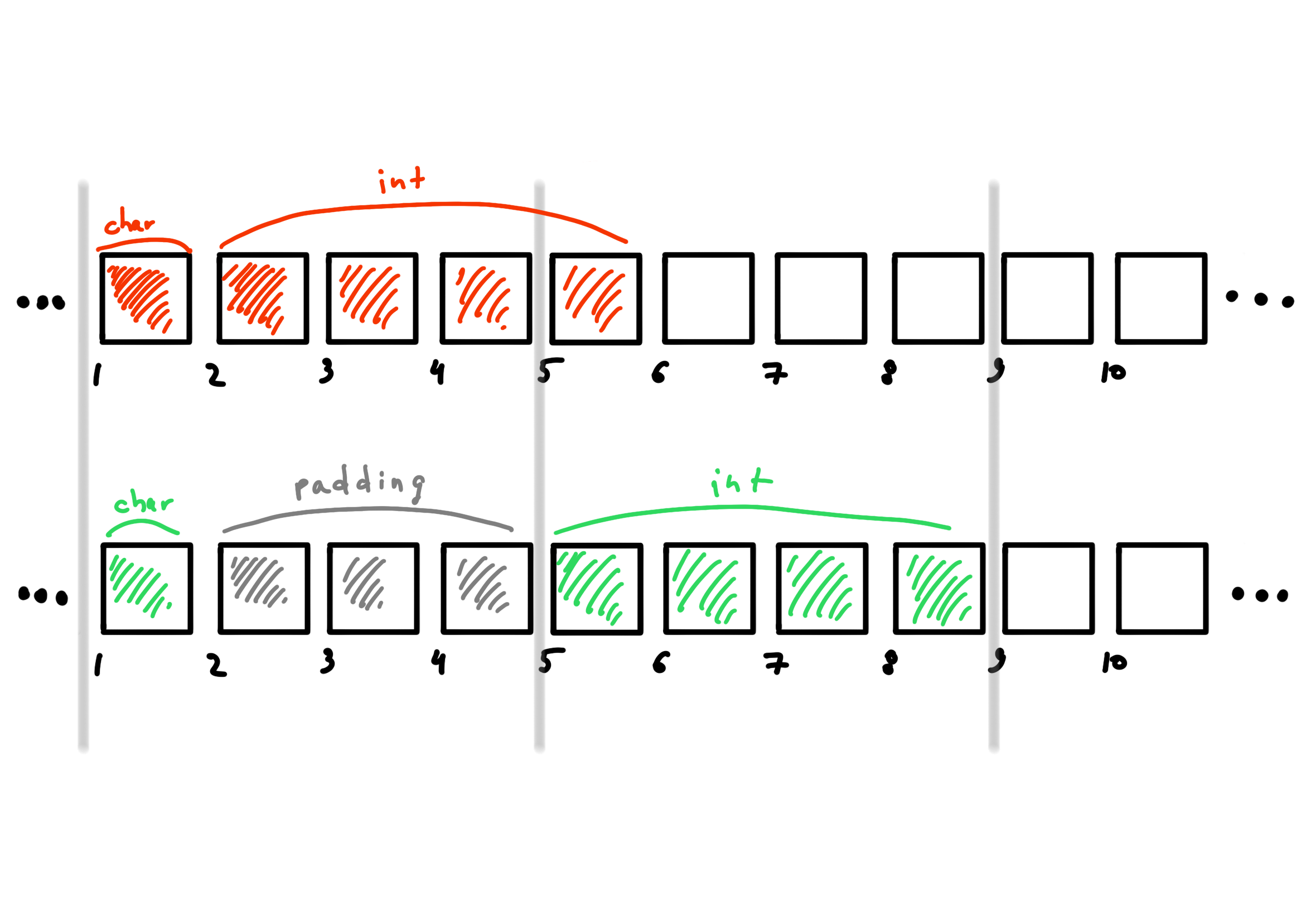

Okay, easy and simple. Although… Stop! What should we do with structures whose fields have different sizes? The requirements for their alignment are different and we can’t store the fields right behind each other. To combat this, we will have to use padding technique. This consists of a) locating the beginning of the structure in a byte whose address is a multiple of the size of the largest field in the structure and b) keeping all fields aligned by introducing “garbage” bytes if necessary.

Example

Suppose we have a MyStruct structure with char and int fields. The first field must be located starting from the byte divisible by 4 (because of the peculiarities of reading by quadruples). But the second field can’t follow it because of its alignment requirement! So we have to leave 3 bytes empty! That is, we only use 5 bytes, but take up 8. As much as 37.5% of the allocated space is garbage! Knowing this can be useful, because by rearranging the fields we can compress the space occupied by the structure! Why this is so - see example below.

struct MyStruct {

char my_char;

int value;

};

to efficiently store fields of complex structure.

Example

# the size of this structure is 12 bytes

struct MyLargeStruct {

char first_char;

int value;

char second_char;

};

# but the size of this structure is only 8 bytes

struct MySmallStruct {

int value;

char first_char;

char second_char;

};

For the MyLargeStruct structure, we need as many as 6 additional padding bytes! The first 3 are for aligning the value field on a multiple of 4. But besides that we need 3 bytes after the last char. Why? It’s not so trivial anymore. Suppose we want to create an array with elements of this structure. To support field alignment of all objects at once and easy addressing, it is very convenient to keep the size of the structure divisible to the size of its largest field. In our case, the size of the largest field is 4, and we have to add 3 bytes of alignment at the end. But for MyStructSmall, we only need 2 bytes of padding at the end of it. That is, just by rearranging the order of the fields, we took 3 times less additional bytes!

Bloom filter

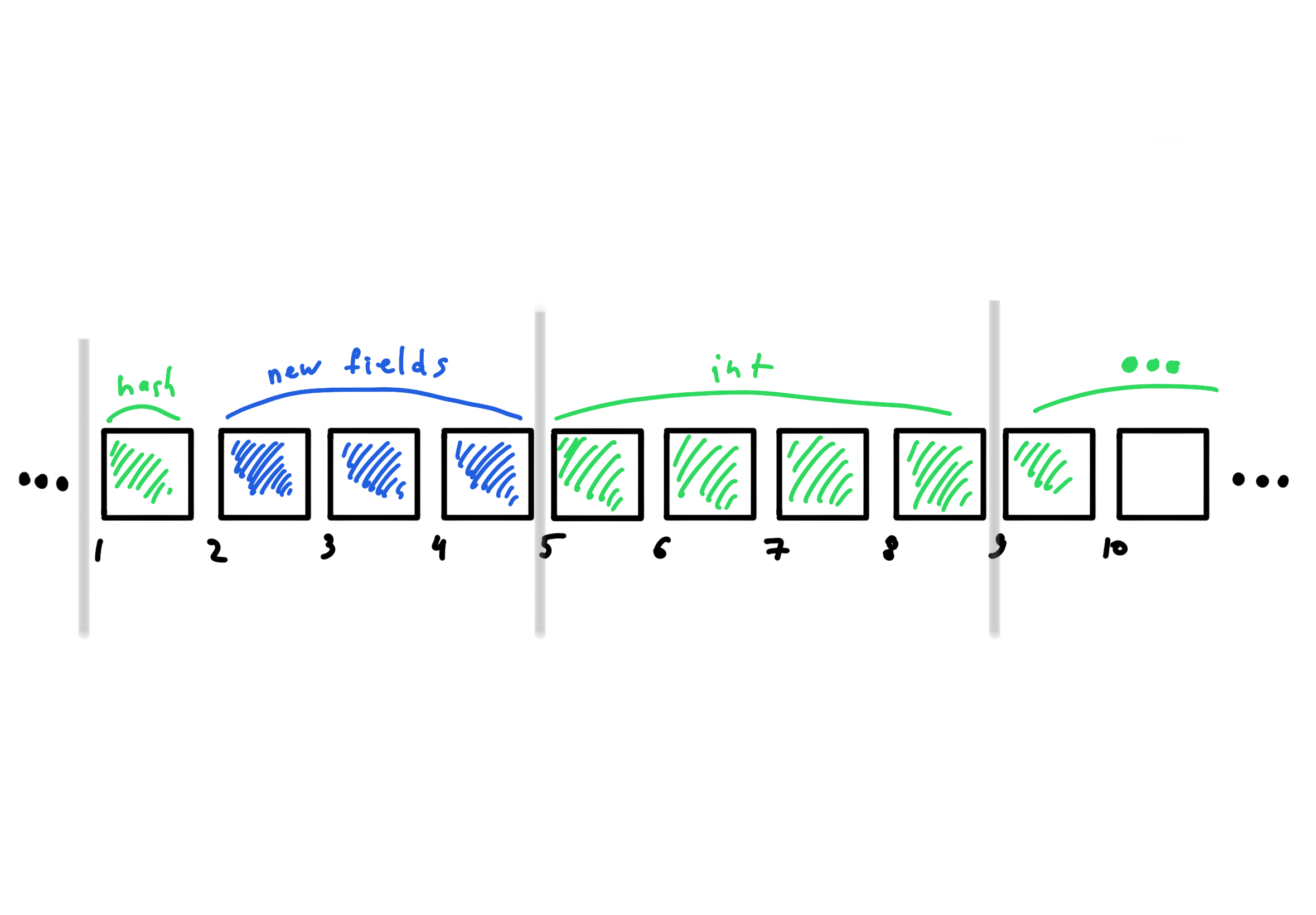

Even with the most efficient data arrangement, in some cases we will have unused memory space due to the hardware architecture. This means that we can occupy it with something useful! For example, add new fields in those places that will be occupied anyway.

the efficiency of an algorithm. For example, we can add new

fields in places where padding will be used anyway.

In practice I faced such a situation when fields of my structure were hash values of some object. My structures were often used for expensive comparison of objects, which was often avoided by hash matching check. By introducing fields with the values of other hash functions, I was able to significantly reduce collisions. In fact, I turned my comparison algorithm into something very similar to the Bloom filter. This improved my system performance, and I didn’t waste a single byte of extra space !

Some might argue: “Why would You go off in the direction of the Bloom filter? Ok, You have more space, take a more complex hash function. You might even have fewer collisions with it!”. Yeah. Thanks for the idea, but for backward compatibility, I had to leave the previous field as it is. That’s the main beauty of this approach - with the help of memory management knowledge You can add new functionality to Your structure without any overhead and consequences!

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: